Valentin Serov, 1901

Self-portrait.

Serov regarded every phenomenon through mistrusting eyes. Whether examining a human being or a new technique in painting, he did so sceptically, analytically.

Once he had formed an opinion, he proceeded in a straight line, undeterred by the vagaries of fashion or the wishes of his sitters. In this respect he was unquestionably both leader and reformer - though he had no wish to lead. In his work, he was strikingly individualistic and stubborn.

He greatly resembled his father, Alexander Serov, composer and philosopher, who approached any contemporary development in music and culture with caution and invariably had his own keen and ironic perception of all things. In the words of Kipling, he was "The Cat That Walked By Himself'. His irony was not sheer scepticism, was not indiscriminate but directed solely against things he disliked.

Valentin Serov himself was a past master at irony, which he used as a protection against any temptation to stray along some unchecked, unanalysed path. But because of this same mentality, he never made his own conclusions obligatory principles for others.

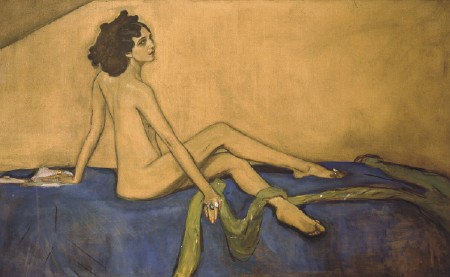

The dancer Ida Rubinstein

by Valentin Serov,

Russian Museum, Saint-Petersburg.

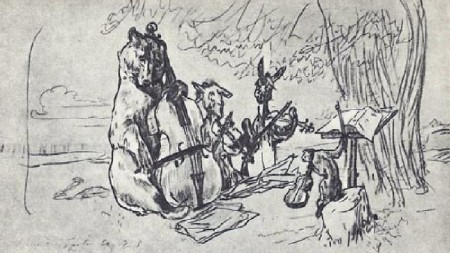

His drawings of animals are remarkable. He was at ease with them - investing them with human traits, engaging in a little satire, getting to the heart of the matter without a single inessential stroke. His wealth of illustrations to Krylov's fables comprise a series of what may be called "Portraits of Imaginary Characters", which fully reflect his ideas on people.

When in Moscow in 1888 he exhibited two portraits, one of V. S. Mamontova (Girl with Peaches) and another of M. Y. Simonovich (Girl in Sunshine), the impression created was startling. They were miracles of beauty, with the realism of the old masters and a modern feeling for colour and sunlight. Nevertheless, all his further work was against the stream. Again and again he reviewed all the possibilities inherent in drawing - which he considered one of the greatest activities devised by mankind.

He posed the "thinking" graphic line against the "sweetly intoxicating" riot of colour. For behind the colourful brilliance of contemporary artists there was too often nothing but a childish infatuation with colour, and a mediocre mentality.

Serov's irony derived from common sense - which is why it was not directed at every element of life around him. Whenever his eye was caught by a typically Russian landscape, a glimpse of rustic life, children or animals, his paintings were tender and trusting - but never maudlin.

To people of whose integrity in work and life in general he was convinced, his attitude was always sympathetic. He could never treat Pushkin with irony. I am always particularly moved by his image of Pushkin in the autumn gloom, on horseback, himself the hero of a romantic ballad. It seems to me that no one has better understood the heart of the poet than Serov.

It is in such paintings that one begins to see past the armour of intellect and irony another facet of the artist's work: joy at the percep tion of integrity. This is true of his famous portrait of Peter the Great, that imperiouis builder and master of life, carried away by his own tempestuous energy. Although there is a tinge of irony here, in this almost frenzied figure, Serov reveals a subtle feeling for history and involuntary admiration for so powerful a personality. Defying all the laws of static painting, his Peter seems to move as though he is leading not a pitiful crowd of hangers-on, barely able to keep up, but a whole country reluctantly yielding to his efforts.

Serov's paintings do not fit into any one genre. Neither his Pushkin nor his Peter is portraiture or descriptive characterization. His rustic scenes are really not' scenes but symbolic, profoundly thoughtful generalizations. It is clear, of course, that his heart is with this genuine rustic mood, not with the society people whose portraits he painted.

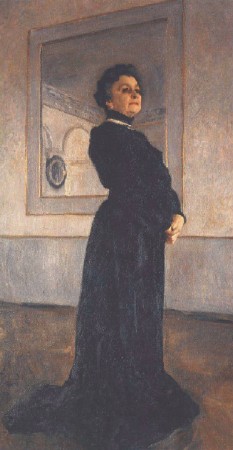

Portrait of M. Yermolova

by Valentin Serov,

Tretyakov Picture Gallery, Moscow.

Serov's portraits are of people of definite social standing whose class demands they maintain a pose. Such is his celebrated painting of Girshman. The artist subtly noted the pose of the wealthy art patron and did a very realistic but extremely satirical portrait. No wonder people said it was dangerous to have one's portrait painted by Serov.

His picture of the art critic D. V. Stasov is that of a typical, intellectual lawyer, and, moreover, a faded and aged man. Had he been depicted discussing some memorable contemporary, say Glinka or Berlioz, or handling a cherished book, or listening to music, or himself playing the piano, the colourless old man would have revealed youthful emotion. But Serov chose to paint Stasov in the characteristic role he assumed in his own circle. As a result the portrait is true, but the person portrayed is only half alive, half presented.

In painting Chaliapin, Serov could not refrain from subtly underlining the great singer's height, so imposing on stage, yet somewhat absurd when clad in frock-coat. Connoisseurs are accustomed to praising his portrait of the actress Yermolova. However, Serov emphasized the actress more than the woman. In addition, owing to the incoherent background, he robbed the celebrity of the stateliness she would have displayed had the background been one unobtrusive entity.

Serov's gallery of portraits, though definitely realistic, should not trap the unwary into accepting his characterization of the people concerned. One must bear in mind the artist's own, highly individualistic style, plus his sceptical attitude to the human ego and his suspicion that unusual qualities meant posturing.

His art is fascinating if looked at from the viewpoint of his constant restlessness and discontent with his achievement. On the other hand, anyone who thinks line and form no more than formal categories, will find the artist's creative methods unrewarding.

Arts by Valentin Serov

Mika Morosov (canvas, oil)

by V. A. Serov, 1901.

Tretyakov Picture Gallery, Moscow.

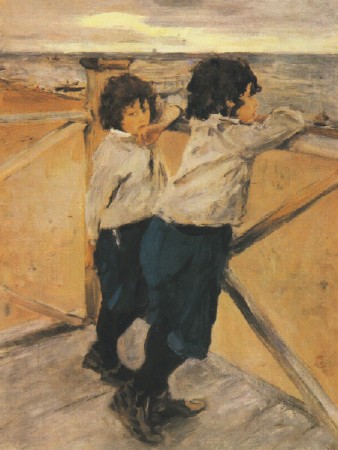

Children (canvas, oil),

by V. A. Serov, 1899.

Russian Museum, Saint-Petersburg.

Girl in Sunshine, 1888.

Tretyakov Picture Gallery

Russia, Moscow.

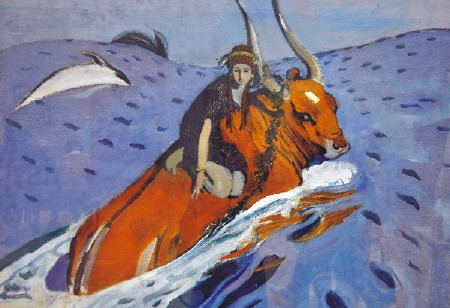

The Rape of Europa.

From the Serovs' family collection.

Illustration to the fable

«Wolf and crane» by Krylov.

Illustration to Ivan Krylov's

fable «Quartet».

Illustration to Krylov's

fable «Crow».